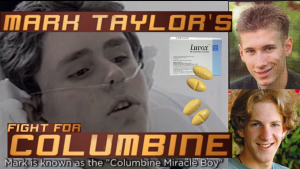

Columbine: Anatomy of a Coverup

Days after the Columbine shootings, Jeffco officials were already lying about what they knew. What about now?

April 30, 1999:

- JCSO lieutenant John Kiekbusch (center)

- Jeffco DA Dave Thomas (right)

- Sheriff Stone did not appear

tell the official story of Columbine at a press conference.

Anatomy of a Coverup

Days after the Columbine shootings, Jeffco officials were already lying about what they knew. What about now?

By Alan Prendergast

Originally published: September 30, 2004

It took five years, a state grand jury and key evidence from a reluctant witness, but families who lost children in the attack on Columbine High School finally had their worst suspicions confirmed: Top Jefferson County leaders knew something awful about prior police investigations of killers Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, and they’d known it since shortly after the 1999 shootings.

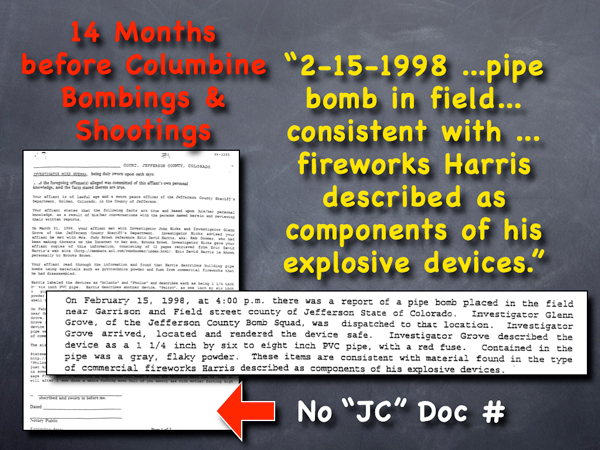

Excerpt from Bomb Search Warrant:

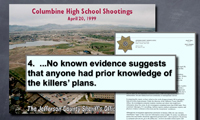

The officials knew plenty, denied most of it, and hid as much as they could for as long as they could. Called by Colorado Attorney General Ken Salazar, the grand jury released a summary of its findings two weeks ago. Although the probe of missing police documents resulted in no indictments, it did raise questions about “suspicious” actions by theJ efferson County Sheriff’s Office brass, including the shredding of a large pile of Columbine files.

The officials knew plenty, denied most of it, and hid as much as they could for as long as they could. Called by Colorado Attorney General Ken Salazar, the grand jury released a summary of its findings two weeks ago. Although the probe of missing police documents resulted in no indictments, it did raise questions about “suspicious” actions by theJ efferson County Sheriff’s Office brass, including the shredding of a large pile of Columbine files.

Most stunning of all, the report charged that a few days after the massacre, several high-ranking county officials met secretly and resolved to suppress key documents stemming from the JCSO’s earlier investigation of Harris, to treat them as if they didn’t exist — in short, to lie about them.

“It’s amazing,” says Brian Rohrbough, whose son, Dan, died on the steps of Columbine. “While we were planning a funeral, these guys were already planning a cover-up.”

Several former and current county officials have disputed the grand jury report, including District Attorney Dave Thomas, who attended the private meeting but has disavowed any role in the subsequent cover-up. (Thomas is now running for Congress, and the Colorado Democratic Party has bemoaned the fact that he’s the target of a smear campaign by unholy,unnamed forces.)

Yet the trail of duplicity surrounding the Columbine files is far more extensive, and disturbing, than the report indicates. In their quest to protect their own hides and careers, a pack of Jeffco bureaucrats misled victims’ families and the public, trashed the state’s public-records law, and thumbed their noses at civil subpoenas and court orders. The conspiracy of silence held fast for 64 months, until the threat of criminal prosecution finally cracked it. Why would so-called public servants do such a thing? The delicately worded grand jury report doesn’t delve into such matters, but it’s clear that the county had a major public-relations and legal nightmare on its hands on April 20, 1999, and that some officials were grappling with it even before the smoke and screams had dissipated at Columbine. Thirteen people were dead,another two dozen wounded, all at the hands of Klebold and Harris — who’d been the subject of several complaints to local police over the previous two years.

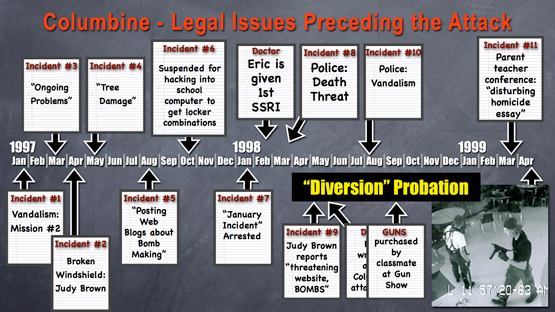

Some aspects of the pair’s contacts with law enforcement, such as their 1998 arrest for burglary and participation in a juvenile diversion program run by the district attorney, were bound to come out soon. But the most embarrassing case was one that never led to a prosecution: The reports filed by Randy and Judy Brown against Harris, who’d boasted on his website about blowing up pipe bombs and had threatened to kill the Browns’ oldest son, Brooks.

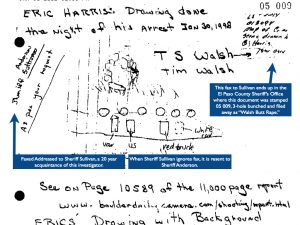

Almost a year before the shootings, JCSO bomb investigator Mike Guerra looked into the matter, even drafting an affidavit for a warrant to search Harris’s home. But the warrant was never submitted to a judge, and the investigation was abandoned after Guerra was reportedly told by a supervisor, Lieutenant John Kiekbusch, that he didn’t have enough evidence to proceed.

Given the arsenal in his room, as well as writings dealing with the planned attack on Columbine that Harris was assembling a year before the shootings, it’s possible that pursuing the search warrant could have averted the whole tragedy (“I’m Full of Hate and I Love It,”December 6, 2001).

Several JCSO officials were evidently briefed on Guerra’s affidavit hours after the shootings. Former undersheriff John Dunaway told Salazar’s investigators that he discussed the affidavit with District Attorney Thomas as early as the day of the attack. He thought he had “several discussions” with Thomas about the matter over the next few days, in which Thomas assured him that Guerra never had probable cause for a warrant. At the same time, investigator Kate Battan used material from Guerra’s investigation to help prepare the search warrants that were served on the Harris and Klebold homes after the attack; sealed by court order, those warrants weren’t made public for several more years.

A few days after the shootings, according to the grand jury report, the upper echelon of the sheriff’s office — including Sheriff John Stone, Dunaway, Kiekbusch, public information officer Steve Davis and the hapless Guerra — met quietly with Thomas, Assistant DA Kathy Sasak,County Attorney Frank Hutfless and two of his assistants, William Tuthill and Lily Oeffler, and others.

The meeting was held in an out-of-the-way Jefferson County Open Space office, and the principal item on the agenda was Guerra’s affidavit. Reporters were already sniffing around the Brown complaint; the JCSO had first denied that any report was taken, then decided to release it, minus the subsequent investigative paperwork.

By the end of the meeting,authorities had decided that they would not disclose the existence of the Guerra affidavit,either. Thomas maintains that he was at the meeting simply to render an opinion on the probable cause issue; he insists he didn’t know of the decision to suppress the document. But in the days that followed, the sheriff’s office didn’t just omit mention of the affidavit. Their people lied about what the Browns told them and the extent of their investigation of Harris,misleading the world press about it all. And Dave Thomas went along for the ride.

At a press conference on April 30, Steve Davis read a press release that purported to explain what deputies did in response to the Browns’ complaints about Harris. The statement, drafted by Lieutenant Jeff Shrader, was the start of a long-running disinformation campaign targeting the Browns. It contained several statements that simply weren’t true, some of them flatly contradicted by the information in Guerra’s affidavit. But then, nobody was going to mention that damning piece of paper. (Stung by the grand jury’s criticism of his role, Shrader issued a response of the I-was-only-following-orders variety: Since County Attorney Hutfless and Thomas both thought Guerra’s affidavit wouldn’t stand up in court, “Mr. Shrader gave due deference to the conclusions of these officials.”)

Fielding questions from reporters, Kiekbusch reiterated some of the same falsehoods. No, the investigator hadn’t been able to find any pipe bombs in the county that matched Harris’s description of the ones he was building. (Guerra had found one.) No, there was no record that the Browns had met with investigator John Hicks. (The affidavit noted the meeting.) No, the investigators hadn’t been able to locate information about Harris on the Internet. (Guerra would later tell Salazar’s people that a JCSO computer expert had been unable to access the website but did find Harris’s AOL profile.)

The man who by some accounts had pulled the plug on Guerra’s investigation was now assuring everyone there was no investigation worth mentioning. District Attorney Thomas stood at the podium with Kiekbusch and Davis and took it all in,then answered some questions himself. At no point did he contradict the torrent of mendacity flowing from the sheriff’s office — which he knew to be mendacity, evidently, having been consulted on the Guerra affidavit extensively at this point.

Instead, Thomas added to the misinformation, stating that prior to the shootings, no one had connected the pipe-bomb case to the two youths who were in his diversion program. This is one of the biggest remaining myths about Columbine. Actually, Hicks had mentioned the prior burglary case to the Browns; Guerra recalls finding the case in his own check of Harris’s record (despite the JCSO claim that Harris cleared the computer check); and an investigator from Thomas’s own office had found the burglary case in 1998 after being contacted by Judy Brown about the pipe bombs.

Yet even though the kid making bombs and death threats was already on probation, nobody did anything about it. “I think it’s very difficult and painful to look back and ask a lot of questions about what could have prevented this,” Thomas told the assembled press. But Thomas was hardly alone in his complicity.

Over the next two years, the Browns and news organizations filed numerous open-records requests with the county attorney, trying to track down the missing pieces of the reports generated by the Browns’ complaints about Harris. Tuthill and Oeffler invariably responded that the documents did not exist, that everything connected with the Browns’ complaints had already been released.

Lawyers preparing civil suits on behalf of victims’ families got the same response. Actually, copies of many of the records in question had been provided to the county attorney shortly after the shootings, in anticipation of future litigation — and then locked away. County Attorney Tuthill, who replaced Hutfless in 2001, had no trouble locating his office’s copies of the “missing” records when the attorney general’s investigators came calling a few months ago. The Browns also requested an internal investigation from the sheriff’s office, in an effort to clear up discrepancies in their record hunt and the rumors they were hearing of a botched search warrant. As the Browns recall it, the officer handling the probe seemed more interested in pumping them to find out where they’d heard that such a document existed.

In a letter dated August 14, 2000, Undersheriff Dunaway airily dismissed their complaint: “There is no indication that anyone tampered with or withheld entry of information related to Eric Harris. “Months earlier, Kiekbusch told Westword that the records the Browns were after had either been routinely purged from the system or had never existed.

But that was long before the files would have been purged, under the JCSO’s record-retention policy, and no one has ever been able to explain why the department would purge records that had some bearing on the largest criminal investigation in Colorado history.

In any case, the “purged files” explanation was just another piece of misdirection; the grand jury learned that the sheriff’s office had kept copies of the documents, too, and had withheld them — even, apparently, from Stone’s successors as sheriff, Russ Cook and Ted Mink — until Salazar’s men examined them last January.

The hide-and-seek game over Guerra’s affidavit continued until the spring of 2001, when producers from 60 Minutes II, armed with concrete proof that the affidavit existed, went to court to demand its release. (Point of disclosure: I served as a paid consultant to CBS News on the project and was involved in that court battle.)

The proof came, oddly enough, in a letter Dave Thomas had recently sent to the Browns; after taking a leisurely five months to respond to their demands for a grand jury probe of the missing files, Thomas spilled the beans by acknowledging that “a search warrant draft was started” by Guerra.

Braced by 60 Minutes II about the letter, a befuddled Thomas said he was under the impression that the Guerra affidavit was old news. To the chagrin of the county’s attorneys,Judge Brooks Jackson ordered the document to be released.

The JCSO tried to save face with an Orwellian press release that declared, “A few days after the Columbine shootings, the Sheriff’s Office disclosed the existence of the so-called ‘secret’ search warrant affidavit” –when, in fact, what had happened was a conspiracy not to disclose it (“Chronology of a Big FatLie,” April 19, 2001). But other documents remained hidden. It was part of a larger campaign of obfuscation and outright deceit that encompassed not only the prior investigation of Harris, but the police response to the attack; timelines were distorted or destroyed, dispatch logs and other vital evidence deep-sixed (“In Search of Lost Time,” May 2, 2002).

As long as the lawsuits against the county filed by victims’ families were stopped dead in their tracks, what difference did it make how this was done?In an effort to dispel the suspicion that the county was, um, hiding something, two years ago Thomas and Salazar agreed to co-chair the Columbine Records Review Task Force, an effort to see what remaining confidential documents from the investigation might be released.

Unfortunately, several members of the task force — notably, Thomas, Sasak, Oeffler and Battan– were perceived as having a stake in not disclosing Columbine’s remaining secrets. Oeffler andBattan soon resigned from the task force, while Thomas and Sasak soldiered on.

But it wasn’t the task force that uncovered the secret meeting and the lies that followed. Last fall, a 1997 police report on Harris suddenly surfaced, prompting a mortified Sheriff Mink to ask Salazar to investigate. Over the course of two interviews, Guerra offered investigators somewhat contradictory accounts of what he’d done and who he’d shown his affidavit to.

In a third interview, he finally acknowledged the Open Space meeting and its purpose. It was “kind of one of those cover-your-ass meetings, I guess,” he said. Guerra said he was told not to discuss his affidavit with anyone outside the county attorney’s office.

His file disappeared from his desk for a few days, then reappeared. His affidavit was mysteriously deleted from his computer files, but he suspected that other people at the meeting kept their own copies. Stone, Dunaway and Kiekbusch are no longer at the sheriff’s office. All have emphatically denied any wrongdoing; contrary to the recollections of Guerra and another officer, Kiekbusch told investigators he never saw Guerra’s affidavit until after the shootings.

Thomas and Oeffler didn’t respond to requests for comment. The Browns say they’re grateful that the grand jury released its report, but they’re also frustrated with the narrow scope of the investigation. “It’s unbelievable that you can have this much evidence of a cover-up and yet no criminal charges,” says Randy Brown. “People who were in that meeting lied about my family and what they knew for five years.”

Missing flash video:

Original – Archive http://columbinefamilyrequest.org/2010/01/columbine-anatomy-of-a-coverup/

Responses to “Columbine: Anatomy of a Coverup” http://tipggita32.wordpress.com/2011/01/13/columbine-anatomy-of-a-coverup/

Columbine: Anatomy of a Coverup

January 13, 2011 by bjjangles

Days after the Columbine shootings, Jeffco officials were already lying about what they knew. What about now?

By Alan Prendergast

Originally published: September 30, 2004

It took five years, a state grand jury and key evidence from a reluctant witness, but families who lost children in the attack on Columbine High School finally had their worst suspicions confirmed: Top Jefferson County leaders knew something awful about prior police investigations of killers Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, and they’d known it since shortly after the 1999 shootings.

The officials knew plenty, denied most of it, and hid as much as they could for as long as they could. Called by Colorado Attorney General Ken Salazar, the grand jury released a summary of its findings two weeks ago. Although the probe of missing police documents resulted in no indictments, it did raise questions about “suspicious” actions by the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office brass, including the shredding of a large pile of Columbine files.

Like this:

Be the first to like this.

Filed under: Accidents and Assassinations, conspiracy, Police State, Spying/Secret Services, Terrorism